mission & vision.

Serving Humanity, Upholding Dharma

Mission

At Karma Nishtha Sanatan, our mission is to serve humanity through selfless action (Seva), guided by the values of Dharma (righteous duty) and Karma (cause and effect). We strive to provide disaster relief, uplift the underprivileged, and empower individuals through skill development and self-reliance. Rooted in Sanatan traditions, we work toward a harmonious society where everyone has the means to live with dignity and respect.

Vision

Our vision is to create a world where service and righteousness lead to holistic well-being. Inspired by Bharat’s rich heritage, we aim to preserve cultural values, promote ethical living, and ensure that every individual can contribute meaningfully to society. Through initiatives like Gaushala, Sanatan Food Hub, and sustainable livelihood programs, we foster a compassionate, self-reliant, and spiritually enriched community.

why us.

What Makes us Different?

Dharma

Dharma is the foundation of a just and ethical society. It is one’s moral duty, shaped by age, role, and circumstances, ensuring both personal integrity and societal balance. By upholding Dharma, we foster harmony, righteousness, and collective well-being.

Karma

Our actions shape our present and future. Karma teaches us that every deed has consequences, guiding us toward ethical living. By engaging in selfless service and righteous actions, we create a positive impact on individuals and society at large.

Moksha

The ultimate purpose of life is Moksha—freedom from the cycle of birth and death. Through selfless service, devotion, knowledge, and righteous action, we aim to uplift ourselves and others, leading to spiritual liberation and a higher consciousness.

Seva

Rooted in the principle of service before self, Seva is at the heart of our mission. We are committed to serving those in need, providing disaster relief, supporting the underprivileged, and uplifting communities through skill-building and livelihood programs.

Ahimsa

Inspired by Sanatan values, we uphold Ahimsa, the principle of non-violence and compassion. Our initiatives, including Gaushala and sustainable living projects, reflect our commitment to preserving life, protecting nature, and fostering kindness in all aspects of life.

Sanskar

We draw strength from Bharat’s rich heritage and Vedic wisdom. By promoting ethical living, traditional knowledge, and spiritual values, we inspire individuals to lead meaningful lives, rooted in the timeless principles of Sanatan Dharma.

HEROS

Legend Who Inspire Us

Let’s start the journey towards success and enhance revenue for your business.

Bhagat Ravidas ji

Sant Ravidas ji is one of the most revered saints of India. He was born in a family of shoe maker, but his teaching went beyond the barriers of caste and distance. He preached the prime importance of karma and devotion. He spent most of his life in Kashi, but his teachings are popular all over the world. His hymns form an essential part of Shri Guru Granth Sahib.

Sant Namdev ji

Sant Namdev ji was born in Maharashtra in a tailor family. His bhajans and poems written in Marathi language in the 13th century are still popular. In Maharashtra the followers of Varkari tradition based in Pandharpur are his ardent followers while in punjab Sikh community pays him respect by including his teachings in Shri Guru Granth Sahib. His works include both Nirguna and Saguna forms of Bhakti.

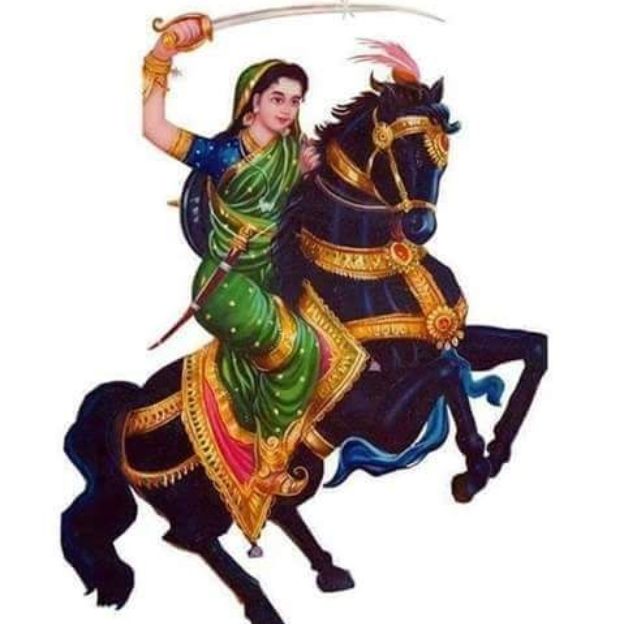

Kittur Rani Chennamma

Rani Chennamma the queen of Kittur, in Karnataka was a brave warrior queen who fought gallantly against the British East Indian Company. The company wanted to seize control of her kingdom. Tales of her courage continue to inspire current generations and are a testament to the mettle of Indian women and their respectable position in Indian culture.

Mata Gujari Devi

Wife of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Mother of Guru Gobind Singh. She accompanied the younger two sahibzaade Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh when they were imprisoned in Sindh. She was a brave mother who instilled the religious values in her son and grandsons, who were ready to sacrifice everything while taking stand for Satya and Dharma.

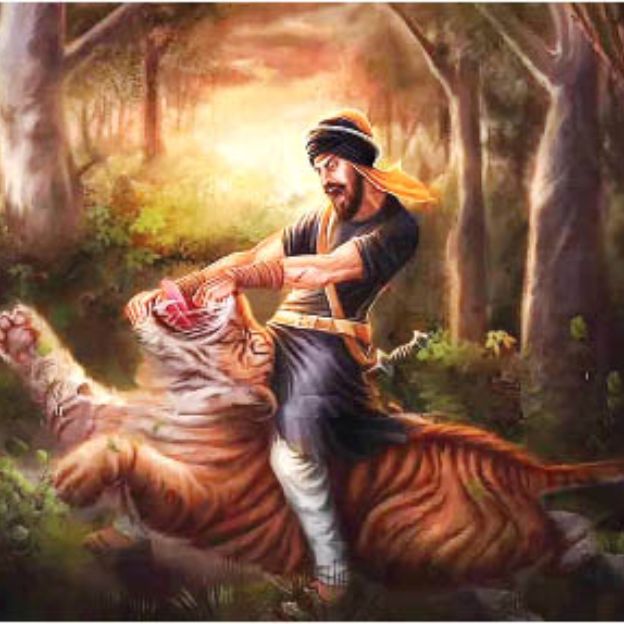

Hari Singh Nalwa

Hari Singh Nalwa (29 April 1791 – 30 April 1837) was the commander-in-chief of the Sikh Khalsa Fauj, the army of the Sikh Empire. He is known for his role in the conquests of Kasur, Sialkot, Attock, Multan, Kashmir, Peshawar and Jamrud. Hari Singh Nalwa was responsible for expanding the frontier of Sikh Empire to beyond the Indus River right up to the mouth of the Khyber Pass.

Shri Aurobindo

Shri Aurobindo was a freedom fighter born in bengal, who editted newspaper like Bande Mataram, and was jailed for participation in revolutionary activities which included various bombings. In the jail, after what is referred to as a divine intervention, he took a spiritual turn, becoming a saint and a philosopher establishing an Ashram in Pondicherry. He was twice nominated for the Nobel prize in literature and for peace.

Bhamashah

Bhamashah was a minister in the court of Maharana Pratap of Chittorgarh. When Maharana had to rebuild his army and reclaim the territories that Mewar has lost to the Mughal attacks, he stood up as the biggest financer for the kingdom, donating away his entire wealth earned over various generations for the cause of Nation.

Maharaja Sayaijirao Gaikwad

Vadodara state under the rule of Maharaja Sayaijirao Gaikwad was one of the most welfarist princely state of India during his reign from 1875-1939. He worked for the education of his subjects, uplifting of the downtrodden, and judicial, agricultural and social reforms. He played a key role in the development of Baroda's textile industry, and his educational and social reforms included among others, a ban on child marriage, removal of untouchability, spread of education, development of Sanskrit, ideological studies and religious education.

Banda Bahadur

Shri Aurobindo was a freedom fighter born in bengal, who editted newspaper like Bande Mataram, and was jailed for participation in revolutionary activities which included various bombings. In the jail, after what is referred to as a divine intervention, he took a spiritual turn, becoming a saint and a philosopher establishing an Ashram in Pondicherry. He was twice nominated for the Nobel prize in literature and for peace.

Bhagat sadna ji kasai

Bhamashah was a minister in the court of Maharana Pratap of Chittorgarh. When Maharana had to rebuild his army and reclaim the territories that Mewar has lost to the Mughal attacks, he stood up as the biggest financer for the kingdom, donating away his entire wealth earned over various generations for the cause of Nation.

Philosophies that inspire us

The Essence of Yajna: Balance, Service, and Dedication

Yajna – Restoring Nature’s Balance

- We continuously take from nature; yajna is our way of giving back.

- It involves replenishing resources, maintaining purity, and creating new value through activities like farming, cleaning, and producing essentials.

Dana – Giving Back to Society

- Society nurtures us, and dana is our duty to repay that debt.

- It includes selfless service, financial contributions, and efforts to uplift humanity.

Tapas – Purification of the Self

- Our body, mind, and intellect wear out daily. Tapas is the practice of discipline and self-restraint to cleanse and strengthen them.

Interconnectedness of All Three

- Nature, society, and the body are not separate; their balance is essential for harmony.

- The Gita expands yajna to include dana and tapas, emphasizing selfless action.

Food as Part of Yajna

- Eating is not just consumption but an act of sustaining oneself for service.

- Every action done with this awareness becomes a sacred offering.

Faith and Dedication

- True service is rooted in devotion, seeing all actions as an offering to the divine.

- A life dedicated to selfless service leads to fulfillment and spiritual progress.

The Story: The Brahmin Seeker and the Butcher

- A young Brahmin ascetic, Kaushika, had left his home for tapasya (austerities) in pursuit of spiritual wisdom.

- One day, a bird’s droppings fell on him while he was meditating. In anger, he looked at the bird, and it burned to ashes due to his spiritual power.

- Realizing his newfound power, he felt pride and arrogance in his knowledge and continued on his way.

The Lesson from a Housewife

- Kaushika later approached a housewife for alms.

- The woman was busy attending to her husband and asked him to wait.

- When she finally attended to him, she sensed his arrogance and told him:

“O Brahmin, do not think too highly of your tapasya. I am no ordinary woman, and I know what happened to you and the bird.” - Shocked by her insight, Kaushika humbly asked where she had gained such wisdom.

- She told him,

“Go to the butcher (Vyadha) in Mithila. He will teach you the highest truth of dharma.”

The Teachings of the Butcher (Vyadha)

- Kaushika, still doubtful, reached Mithila and met Vyadha, a simple butcher who sold meat.

- Expecting a spiritual teacher to be an ascetic or a priest, he was shocked to find a butcher in a meat shop.

- Vyadha welcomed him with great respect and said,

“O Brahmin, I know why you have come. Dharma is not about external appearances but about fulfilling one’s duty with sincerity and devotion.”

Key Teachings of Vyadha Gita:

- Dharma (Duty) Above Everything:

- One’s duty (svadharma) is the highest path to enlightenment.

- Vyadha, though a butcher, performed his duty with honesty, sincerity, and without attachment to sin.

- Spirituality in Daily Life:

- One does not need to renounce the world to achieve wisdom; true spirituality lies in how one serves others and performs daily duties with devotion.

- Respect for Family and Society:

- Vyadha explained how he served his parents, family, and society with love, which was as great as any spiritual practice.

- Egolessness and Humility:

- True wisdom comes not from power, pride, or rituals, but from humility, service, and inner devotion.

- Ahimsa (Non-violence in Thought):

- Though Vyadha was a butcher, his intentions and heart were pure, making him more righteous than a Brahmin with pride.